Here on this blog, I’m probably preaching to the choir when I write that the working conditions and wages of a majority of adjunct faculty in higher education are truly shameful: they—we, for I am one, too—often work without offices, without access to office support or supplies, without safe and private places to meet students, without teaching materials, healthcare, benefits, and hope of ever achieving a even a secure, let alone tenured, position. Or maybe we have an overabundance of the latter.

Here on this blog, I’m probably preaching to the choir when I write that the working conditions and wages of a majority of adjunct faculty in higher education are truly shameful: they—we, for I am one, too—often work without offices, without access to office support or supplies, without safe and private places to meet students, without teaching materials, healthcare, benefits, and hope of ever achieving a even a secure, let alone tenured, position. Or maybe we have an overabundance of the latter.

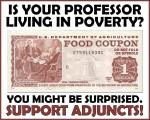

I can think of only one other reason why so many of us have failed to speak in public about the conditions we’re forced to work under, how hard we work, and how little we work for: we fear losing what little we have in our precarity. And for many adjunct faculty, it’s also embarrassing to be so highly educated yet unable to support ourselves. It’s embarrassing to be reliant upon relatives for loans and handouts and “the kindness of strangers” in the form of food stamps, unemployment, and Medicaid—if we can get them. And so we remain silent. This shame seems entirely misplaced to me, as pernicious and self-defeating as being forced to hide one’s sexual identity. So I’m purposefully and respectfully borrowing the language of the outspoken LGBTQ community to urge my fellow adjuncts to end their silence and “come out” to their students, friends, relatives, to everyone, as adjunct faculty members and tell them exactly what that means.

On my first day of classes, I always do two things: I introduce myself by giving my students my educational background and I make sure to tell them that I am an adjunct professor/lecturer/instructor and explain what that means to them in terms of my availability—and in terms of salary. I also make sure they know that the majority of their professors are just like me. And I leave them with a question: what, exactly, is your tuition paying for, if it’s not our salaries? I do this because the makeup of the professoriate has, as we all know, changed drastically since I was an undergraduate in the late 1970s/early 1980s, but the assumptions students make about who is educating them and how they do it are the same ones I had then—though they no longer ring true.

As an undergraduate, I expected my professors to have office hours I could drop into to talk about a paper, about something I didn’t understand in class, about shaping my academic career, about going abroad, about, in short, being a student and everything that means. I had some wonderful, long conversations with my professors about books, travel, graduate school, poetry, and teaching, several of which were truly formative. They’re the same kinds of conversations I’d like to have with my students, and they expect that opportunity of me.  But in at least one institution at which I’ve recently taught, I not only had no office, but I was still expected to “be available” (as my contract explicitly stated) in the hallway outside the classroom for a half-hour before and after each class. In another institution where I currently teach, I share a large office of 5 desks with 25 other adjuncts on a rotating basis, with not even a cubicle divider between us for an illusion of privacy. Who wants to talk to their professor under those kinds of conditions? Especially not to tell her some embarrassing story about how you had to move into a shelter over the weekend to get away from your boyfriend, and that’s why your paper is late (true story).

But in at least one institution at which I’ve recently taught, I not only had no office, but I was still expected to “be available” (as my contract explicitly stated) in the hallway outside the classroom for a half-hour before and after each class. In another institution where I currently teach, I share a large office of 5 desks with 25 other adjuncts on a rotating basis, with not even a cubicle divider between us for an illusion of privacy. Who wants to talk to their professor under those kinds of conditions? Especially not to tell her some embarrassing story about how you had to move into a shelter over the weekend to get away from your boyfriend, and that’s why your paper is late (true story).

The reason I tell my mostly freshman students (and anyone else who will listen) about the existence of adjunct faculty and what it means for them is that I feel I owe them that much honesty, as an educator and as a member of two unions and officer in one local. Caprice Lawless asserts that, unless we speak up about how we are treated, we’re teaching our students that “they will never see their administrators either, and, should one appear, it is likely time to worry. We model for them not to expect too much, once you graduate, from anyone in leadership, for leadership is in a class of its own making and is self-serving.” What we don’t teach them by remaining silent is to be leaders themselves, to speak up against workplace exploitation or other wrongs, to—as Gandhi infamously did not say, but insinuated—be the change they want to see in the world. We may, in fact, even help blind them to the need for change. Worse, perhaps, is that we teach them to be afraid of change, afraid of the power of their own voices.

This inability to speak up has a number of consequences, not just for adjuncts who feel they themselves are powerless. If we ourselves cannot speak about personally experienced inequity, how can we honestly speak about wage inequity and injustice for other workers, from home healthcare aids to Walmart “sales associates” to fast food workers? Indeed, we have no right to ask our students to listen to those voices, when ours are silent. As Lawless asks, whenever we are silent in our students’ presence about our working conditions while teaching them “to recognize cries for justice in essays they study, do those cries fall on deaf ears? Are we are teaching them to be numb to human suffering?” If nothing else, we are teaching them a brand of hypocrisy, that one kind of suffering is worth listening to and speaking about, and another is not.

As an educator in English, part of my job description is to help my students develop critical thinking skills—to fine-tune their BS detectors, and teach them to distinguish not just fact from fiction but truth from advertising and propaganda, to ferret out and recognize biases, including their own. If we cannot act on our own admonitions to look beneath the surface of what is presented and critique our own working conditions, that too is hypocrisy. Whom are we serving by whitewashing the terms of our employment; by staying silent; by pretending one of those two new tenure-track jobs might be ours? Not ourselves, certainly, and not our students. And what, really, do we have to be ashamed of?

Speaking out openly and fearlessly is also something of its own protection. We are exercising our right to free speech and academic freedom to speak about our working conditions and the more publicly and loudly we speak, the harder it is for us to be punished for it without the punishers seeming both petty and guilty—and opening themselves to an increasing number of lawsuits against such retaliation. The more of us do it, the more impossible it is to fire us all.

So, taking a cue from my CUNY colleagues, I’ve made a boilerplate addition to my syllabi informing students that this class (whatever it is) is taught by an adjunct and including a short statement about what that means on the class blog or Facebook page I create for each section of each course, as required reading for their first day’s homework. The first few times I did this, students were surprised, confused, and then, as we discussed adjunct life in class, angry. Now, thanks to the work NFM has been doing (highlighted here soon) and the growing number of adjuncts who are speaking out, students are much better informed about the existence and role of adjuncts.

But they’re not nearly angry enough.

My experience in revealing the state of adjunct employment to my students has convinced me that this is not only the right thing to do, but a necessity. If we want to make allies among our students and their parents—and to save Higher Ed, I believe that’s essential—we have to incite enough anger for them to demand change with us. And that won’t happen if so many of us continue to indulge in the magical thinking that we are the special snowflake who will get the tenure-track job if only we keep our mouth shut.

–Lee Kottner

Reblogged this on The Academe Blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the signal boost, Aaron!

LikeLike

Here’s the problem–you get angry, you speak up, and before you know it you are hauled into the dean’s or chair’s office for some random and unrelated “bad action” on your part and threatened with termination if your behavior does not improve. I contacted the AAUP national office and was told that if I wanted to keep my job, I had to behave exactly as I was told to do because there was no job protection. My colleagues saw that my classes were being taken away and that I was being marginalized, so they retreated.

We need the help of labor unions to act as a buffer between faculty and administrators. If no union is interested in your faculty group (as in my case), or your colleagues block the union, you can find yourself in a very precarious situation. I commend you for your courage, Lee, but I would urge caution.

LikeLike

I agree it’s not always easy and sometimes dangerous. But no more dangerous than enduring the same exploitation forever. If no one speaks up, nothing changes. For the record, unions offer only so much protection. I belong to two, and am an officer in one Local, but that doesn’t prevent me from not being rehired because there are no classes for me. It’s happened to my colleagues who paved the way for me to speak out. I’m fortunate to have a supportive department that they don’t have, which is why I’m standing on this soapbox. And why Full-timers need to speak out for us too, and support us when we do. But I maintain that the more of us who speak out, together, the harder it is to fire us. I’m also never going to get tenure (I have an M.A. and I’m too darn old), so I have no career to protect; it behooves me to speak out because I can. If everybody in your school starts bucking the system and organizing, they can’t fire all of you. Unions don’t protect us. They ARE us. We protect ourselves.

LikeLike

Here’s what I said on my FB page in introducing this excellent posting:

In case you don’t know, I have been an adjunct for my entire ESL teaching career. If you, too, are living this precarious existence, please take the time to read this entire article.

MORE IMPORTANTLY, if you have been a student, are a student, or have a student in American colleges and universities, read this blog

entry and then ASK the institutions of your choice about their hiring practices, the percentage of adjuncts teaching at the institution, and so on. You can also ask the teachers you know. If they are your current teachers, and adjunct, ask them how you can support them within the academic setting.

It is time for the “business model” to get out of academia.

Feel free to use or edit at will.

LikeLike

Thank you for both the support and the signal boost, Rosemary. Couldn’t agree with you more about getting the business model out of academia.

LikeLike

Now that you have revealed to your students that you are an adjunct and a tier or two lower than your full-time or tenure-track colleagues, you had better be careful not to give too many low grades to your students. The reason I say this is because there could be a dark side to coming out as an adjunct (or at least making a big issue of it to them): students with low grades, or grades lower than they think they deserve, can complain that you are unfair and even unqualified because they might perceive you — unfairly — as less worthy and less competent. Status and money have greater importance today to many students than ever before. Sometimes telling them you are an adjunct can put a crack in your armor.

LikeLike

Even at my worst teaching gig I’ve never had this problem. Not that I haven’t had students complain about grades, but it’s never been a factor in whether I’ve been rehired or not–and I’ve definitely flunked students. Some of that may be attributable to the fact that I’m working in union shops now, but even when I didn’t, when I was forthright with my students, and told them I was a hard but fair grader, this was never an issue. I’m honestly not sure if this is luck or if, because everyone knows I “tattle” to my students that constrains them from mistreating me. Again, though, my experience has been that the more “out” I am, the less hassle I get and the less afraid I am.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Gratifying My Ambition.

LikeLike